Rembrandt Etchings – The Good, The Bad and The Ugly

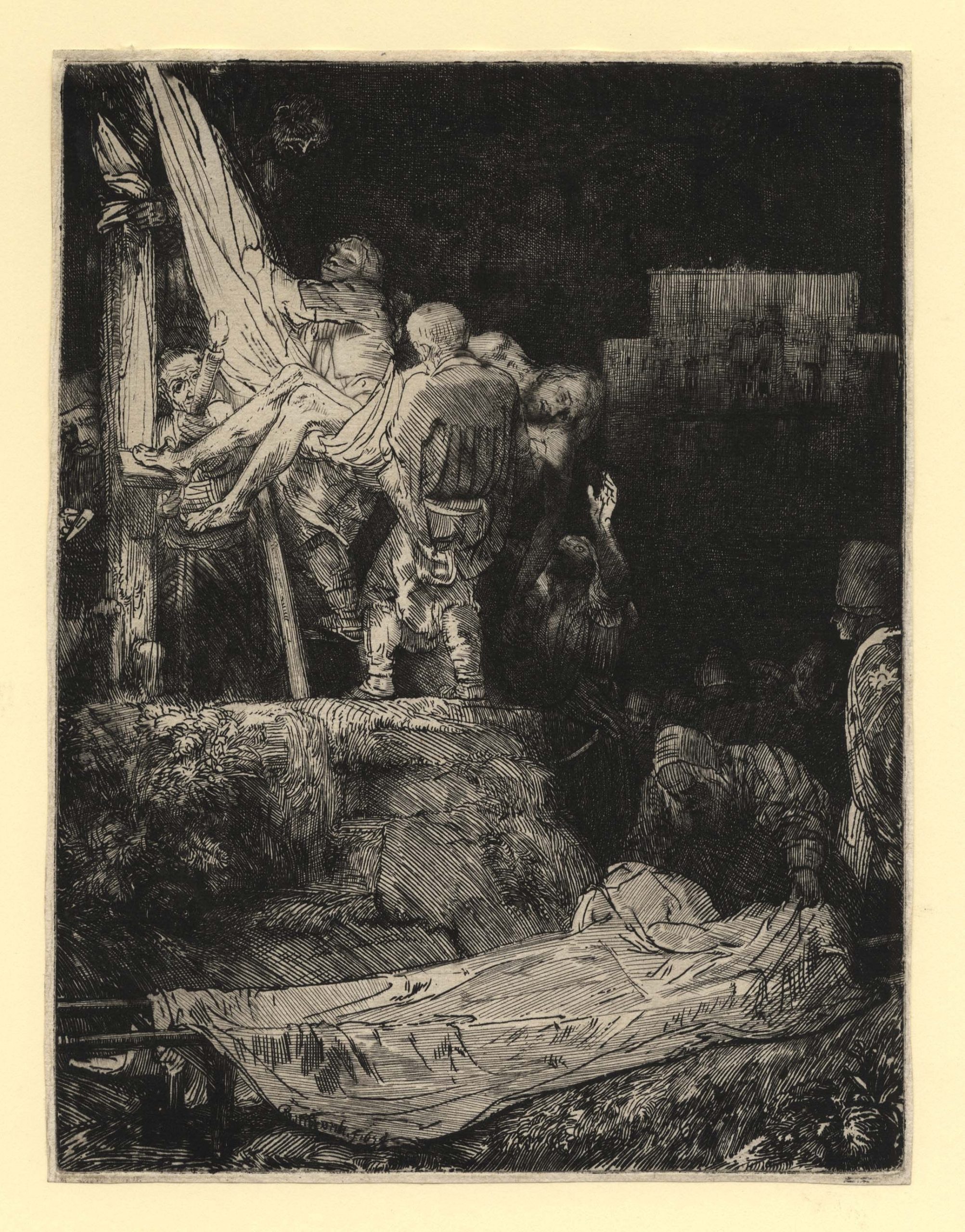

Rembrandt etchings and drypoints, were made working on copper plates, creating ink-holding furrows in these plates either directly (using a drypoint needle) or with etching (drawing through a wax-like substance covering a plate, then bathing the plate in acid to create furrows). At some point in this process he might take an impression to see what his print looks like; he might then change the plate adding some lines or burnishing out lines, check it again (thus creating a new state of the print), do this until he was satisfied with the plate, then print impressions as he cared to, sometimes over a period of years.

Each time a print is made, the copper plate wears down a bit. A shallow drypoint line would wear down quickly; the burr created when the drypoint line was drawn would wear off particularly quickly, losing its capacity to hold ink after perhaps 20 or 30 impressions. Etched lines wear down too. Worn plates make worn impressions.

When he died in 1669, many of Rembrandt etching plates had been cancelled or destroyed, but about 100 were intact. These generally worn plates were then used by others to make more prints, and as the plates became more worn, they were reworked, by successive re-touchers and restorers (their names include Watelet, then Basan, Jean, Bernard, Beaumont (we’re now into the 20th Century!). The evolution of the plates, changes in the lines, reworkings, etc., are fairly well documented. Thousands of these prints (sometimes called re-strikes) are now on the market. Some are still being produced! In many cases they only vaguely resemble the compositions or details that Rembrandt had in mind. They never have the richness, or details, or subtleties of the lifetime impressions.

Traditionally (and still) considered nearly valueless by reputable dealers, Rembrandt etchings restrikes now enjoy a new life on the market, largely due to the presence of huge numbers of internet buyers eager to obtain a real Rembrandt print. Some auction houses sell hundreds of these prints at a time; it’s possible to sit through hours of Rembrandt lots, all with four or five figure sales (i.e, from about $1000 to 10,000 or sometimes more), without encountering a single lifetime impression in the sale.

Because Rembrandt is so well known, many collectors want to start their print collecting career by owning a Rembrandt. But Rembrandt print connoisseurship is particularly involved and complex. Even among the lifetime impressions, some are especially beautiful or striking, some less so. He printed impressions personally, often varying the inks, the paper, the wiping (how much and how selectively he wiped the ink off the plate before printing), and of course made different states. Some great Rembrandt prints are sold for over a million dollars, and all lifetime impressions do and should have a substantial value. In some cases the early states of the prints are well documented, so if it’s clear that Rembrandt himself made changes to a plate, an early state would definitely be a lifetime impression. But sometimes cataloguers include states made after Rembrandt’s death, and if Rembrandt only made one state and never changed the plate, a print called a first state of two or three could be either lifetime or posthumous – this can become a matter of judgement and connoisseurship.

Often people mistakenly pay too much for a common Rembrandt restrike (perhaps misleadingly sold – nicely framed of course – as a lifetime impression), and when they learn about what they’ve done become soured on print collecting. But some go from this early misstep to develop their print knowledge and connoisseurship.

An aspiring connoisseur should see lots of impressions (in the great museum collections) before buying one; should consult with trusted dealers and scholars about any prospective print; should read a number of the catalogues on Rembrandt to get a sense of the evolution of the plate over time. Watermarks may give a sense of when a print was made during Rembrandts’s lifetime, and there are books and articles on Rembrandt watermarks.

But even if one is willing to get into this depth, and then willing to spend large sums, my advice to the beginning collector is to study Rembrandt, but learn about other artists too – there are many ways to get into print collecting and many wonderful artist / printmakers and prints to choose from. For example, wonderful lifetime impressions of prints by Rembrandt’s 17th Century Dutch contemporaries, such as Adriaen Van Ostade, or Cornelis Bega, are available at a fraction of the cost of many Rembrandt re-strikes on the market.

About the author

Harris Schrank is the owner of Harris Schrank Fine Prints specialising in exceptional examples of fine printmaking – original etchings, engravings, lithographs and woodcuts – from 1490 to 1940.