How Prints Made Art Accessible

The Revolution of Reproducibility

The history of art is fundamentally transformed by a single revolutionary concept: reproducibility. While painting and sculpture remained the exclusive domain of wealthy patrons and institutions for centuries, printmaking emerged as the great democratizer of visual culture. From the earliest woodcuts of medieval Europe to the screen prints of contemporary artists, printmaking has consistently challenged the notion that art must be unique, expensive, and accessible only to the elite. This medium transformed art from a luxury commodity into a shared cultural experience, fundamentally altering how societies engage with visual expression and artistic ideas.

The significance of prints extends far beyond their technical innovations. They represent a philosophical shift in how art functions in society, moving from objects of individual ownership to vehicles of mass communication and cultural exchange. Through prints, artistic movements could spread across continents, political ideas could reach the masses, and ordinary people could afford to own and appreciate fine art. This democratization process fundamentally reshaped not only who could access art, but also what art could be and do in society.

The Birth of Mass-Produced Art

The invention of printmaking in 15th-century Europe marked the beginning of art’s democratic revolution. Woodcut printing, the earliest form of printmaking, emerged alongside Gutenberg’s printing press, sharing the same revolutionary principle: that images and ideas could be multiplied and distributed widely rather than existing as singular, unreachable objects. Early woodcuts served practical purposes, illustrating religious texts and popular stories, but they quickly evolved into sophisticated artistic expressions that could reach audiences previously excluded from art ownership.

The technical breakthrough of printmaking lay in its fundamental challenge to art’s scarcity. Where a painting existed as a single object commanding high prices and exclusive ownership, a print could exist in dozens or hundreds of copies, each selling for a fraction of the cost of a unique work. This multiplication didn’t diminish the artistic value of the image; instead, it amplified its cultural impact. A single design could influence thousands of viewers, spreading artistic styles and ideas with unprecedented speed and reach.

Albrecht Dürer, perhaps the first artist to fully grasp printmaking’s democratic potential, elevated the woodcut and engraving to new artistic heights in the early 16th century. His prints achieved the same level of artistic sophistication as his paintings while remaining affordable to middle-class buyers. Dürer’s success demonstrated that prints were not inferior copies of “real” art but a legitimate artistic medium with unique advantages: they could combine fine artistry with broad accessibility, creating a new category of cultural object that served both aesthetic and social functions.

Breaking Down Economic Barriers

The economic democratization of art through printmaking cannot be overstated. In pre-print societies, art ownership was largely restricted to the church, aristocracy, and wealthy merchant classes. Commissioning a painting required substantial financial resources, and the resulting work could only be enjoyed by those with access to private collections or religious institutions. Printmaking fundamentally disrupted this economic model by introducing the concept of affordable multiples.

The price differential between unique artworks and prints was dramatic. While a commissioned portrait might cost the equivalent of a skilled craftsman’s annual salary, a fine print could be purchased for the price of a few meals. This economic accessibility opened art ownership to emerging middle classes, artisans, scholars, and anyone with modest disposable income. For the first time in history, a merchant could own the same image that adorned a noble’s wall, albeit in a different medium.

This economic democratization had profound cultural implications. As print ownership spread through society, artistic literacy increased correspondingly. People who owned prints developed more sophisticated visual vocabularies and aesthetic sensibilities. They became consumers and critics of art rather than merely distant admirers. This expanded audience, in turn, created new markets for artists and publishers, establishing a sustainable economic ecosystem that supported artistic innovation and cultural exchange.

The print market also fostered the development of art as a commercial enterprise rather than merely a patronage-based system. Artists could produce works speculatively, selling them through dealers and at fairs rather than waiting for commissions. This economic independence allowed artists greater creative freedom while simultaneously making their work more responsive to popular tastes and interests.

Geographic and Social Reach

Printmaking’s impact extended far beyond economic accessibility to encompass unprecedented geographic and social reach. Unlike unique artworks that remained fixed in specific locations, prints traveled easily across borders, carrying artistic styles and cultural ideas to remote corners of Europe and eventually to other continents. This mobility transformed local artistic traditions into international movements and facilitated cross-cultural dialogue on an unprecedented scale.

The geographic spread of prints was facilitated by their durability and portability. A woodcut or engraving could survive long journeys better than a painting and could be easily transported by merchants, scholars, and travelers. Print publishers established distribution networks that rivaled those of book publishers, ensuring that successful images reached markets throughout Europe and beyond. This distribution system meant that artistic innovations in one city could influence artists hundreds of miles away within months rather than decades.

Socially, prints penetrated layers of society that had been largely excluded from art consumption. While the nobility collected paintings and sculptures, prints found their way into the homes of shopkeepers, innkeepers, students, and professionals. They decorated taverns, workshops, and modest homes, bringing sophisticated artistic imagery into everyday environments. This social penetration meant that artistic culture became a shared rather than exclusive experience, fostering common visual vocabularies across class lines.

The democratizing effect was particularly pronounced in Protestant regions, where the reduction in religious art patronage following the Reformation created new markets for secular prints. Without the Catholic Church’s massive commissions for paintings and sculptures, artists increasingly turned to printmaking to reach the growing market of private collectors and the emerging Protestant middle class who sought visual culture that reflected their values and interests.

Political and Educational Applications

Prints quickly became powerful tools for political communication and public education, roles that unique artworks could never fulfill due to their limited audience. Political prints, particularly satirical engravings, emerged as an early form of mass media, capable of spreading political ideas and criticisms to broad audiences. These works demonstrated printmaking’s potential not just as democratic art, but as a democratic medium for social and political discourse.

The educational applications of prints were equally revolutionary. Publishers produced series of prints illustrating everything from biblical stories and classical mythology to contemporary events and natural history. These educational prints brought visual learning to audiences who lacked access to illustrated manuscripts or formal education. They served as teaching tools in schools, reference materials in workshops, and sources of general knowledge for curious individuals across society.

Religious prints played a particularly important democratizing role, especially in Catholic regions where devotional images were central to spiritual practice. Inexpensive prints allowed ordinary believers to own devotional images for private prayer and meditation, personalizing religious experience in ways previously available only to the wealthy or religious institutions. These prints made religious art a personal rather than merely institutional experience, contributing to both spiritual and aesthetic democratization.

The political power of prints became evident during periods of social upheaval, when they served as vehicles for propaganda, protest, and reform. The ability to quickly produce and distribute images responding to current events made prints an essential medium for political communication, demonstrating how democratic access to art production could translate into democratic participation in political discourse.

Technical Evolution and Expanding Access

The technical evolution of printmaking continuously expanded its democratic reach. The development of engraving in the 15th century allowed for finer detail and more sophisticated imagery than woodcuts, attracting more affluent buyers while still remaining more affordable than paintings. Etching, introduced in the 16th century, enabled even greater artistic freedom and expression, while mezzotint and aquatint techniques in the 17th and 18th centuries expanded the medium’s tonal possibilities.

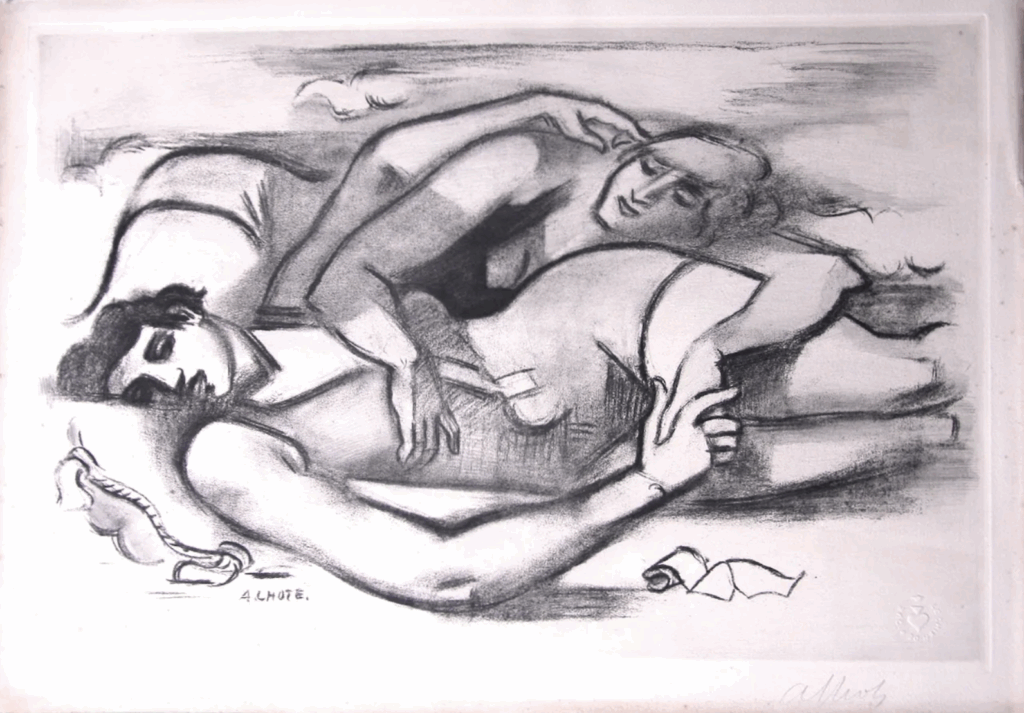

Each technical innovation broadened printmaking’s audience and applications. The invention of lithography in the late 18th century represented perhaps the most significant democratic advance, as it simplified the printing process and reduced production costs even further. Lithography enabled artists to work more directly and expressively while making prints accessible to even broader audiences. The technique’s ease of use also democratized print production itself, allowing more artists to create and distribute their own work.

The industrial revolution brought mechanization to printmaking, dramatically increasing production speeds and reducing costs. Steel engraving enabled much larger editions, while chromolithography introduced affordable color printing. These developments made prints even more accessible while maintaining artistic quality, extending the democratic reach of art into working-class communities that had previously been excluded even from the print market.

Photography’s invention in the 19th century initially seemed to threaten printmaking’s democratic role, but artists adapted by emphasizing printmaking’s unique artistic qualities and expressive possibilities. Rather than simply reproducing reality, prints became vehicles for artistic interpretation and creative expression, maintaining their relevance as democratic art forms even as photographic reproduction made images more ubiquitous.

Modern Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

The democratic principles established by historical printmaking continue to influence contemporary art and culture. Modern screen printing, developed in the 20th century, carries forward printmaking’s democratic tradition while adapting to contemporary artistic needs and markets. Artists like Andy Warhol explicitly embraced printmaking’s democratic potential, using screen printing to challenge traditional distinctions between high and low culture while making art more accessible to contemporary audiences.

Contemporary printmaking maintains its historical role as a democratizing force through community print shops, artist cooperatives, and educational programs that provide access to printmaking facilities and training. These institutions continue printmaking’s tradition of making art production accessible to people who might not otherwise have opportunities to create and distribute visual art.

Digital technology represents the latest evolution in art’s democratization, carrying forward principles first established by historical printmaking. Like traditional prints, digital images can be reproduced infinitely and distributed globally at minimal cost. Online platforms enable artists to reach audiences directly without institutional intermediaries, much as print publishers once bypassed traditional patronage systems.

The democratic legacy of printmaking also influences how contemporary society thinks about art’s role and value. The idea that art should be accessible rather than exclusive, that it can serve social and political functions, and that artistic quality need not depend on uniqueness or high cost all trace back to printmaking’s revolutionary impact on cultural attitudes toward art and its place in society.