Mezzotint

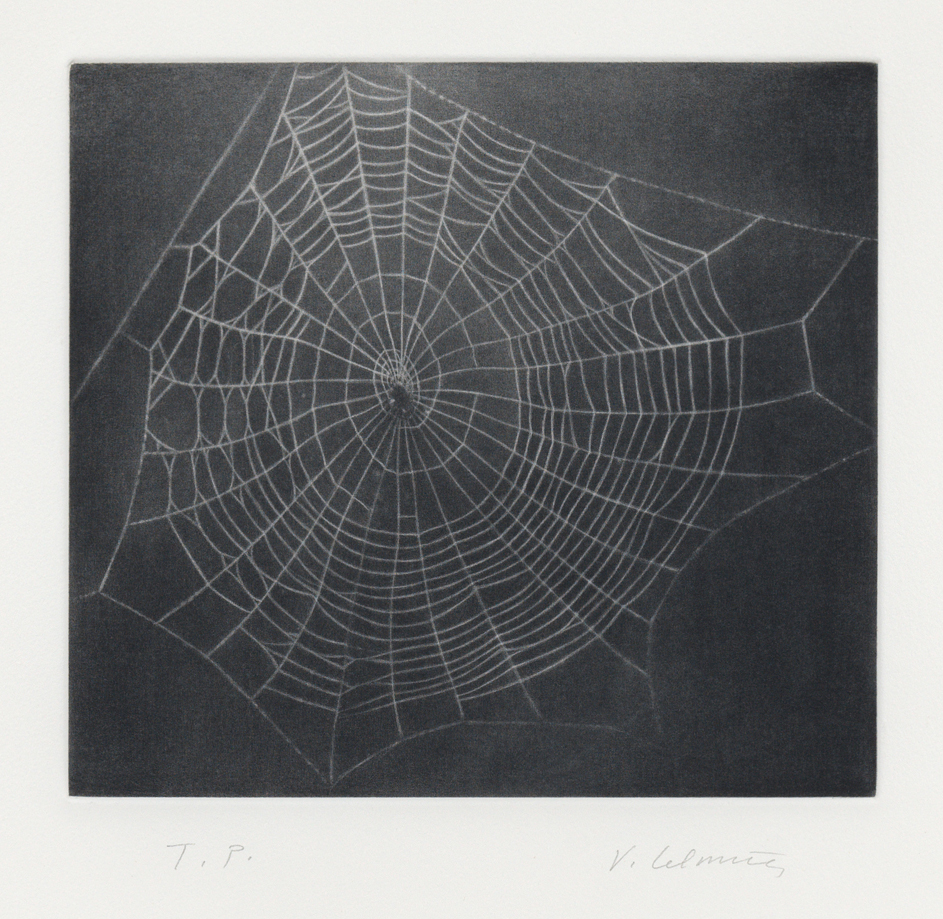

Mezzotint is an intaglio printmaking technique that produces monochrome prints. [2] It was the first printing method to produce half-tones without utilising techniques based on lines or dots, such as stippling, cross-hatching, or hatching. A metal tool with tiny teeth called a “rocker” is used to roughen a metal plate in mezzotint in order to create tone. When a printing plate is cleaned from its face, the microscopic pits in the plate hold onto the ink. This method can produce prints with a high level of quality and richness.

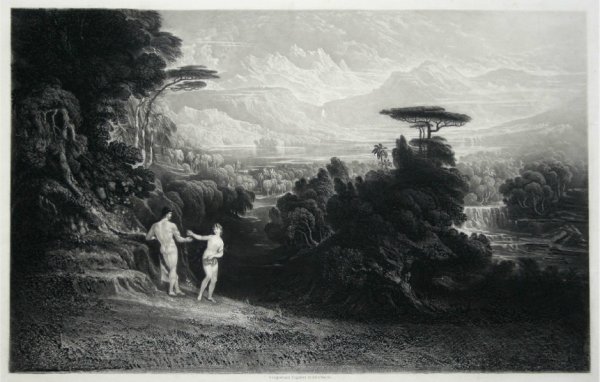

Mezzotint is frequently used in conjunction with other intaglio methods, most frequently etching and engraving. From the seventeenth century, the technique was particularly popular in England for duplicating portraits and other paintings. It was slightly rivalled by aquatint, the second primary tonal technique of the time. Since the middle of the 19th century, it has been employed relatively infrequently because lithography and other processes delivered results that were comparable more quickly. Two noteworthy 20th-century practitioners of the technique are Robert Kipniss and Peter Ilsted; M. C. Escher also produced eight mezzotints.

Ludwig von Siegen, a German amateur artist (c. 1609–c. 1680), developed the mezzotint printing technique. His first mezzotint print, a portrait of Countess Amalie Elisabeth of Hanau-Münzenberg, was created in 1642. Working from light to dark, this was constructed. Prince Rupert of the Rhine, a well-known cavalry leader in the English Civil War, is thought to have invented the rocker. He was the next to employ the method and brought it to England. Sir Peter Lely pushed several Dutch printmakers to go to England because he saw the potential for using it to promote his pictures. Godfrey Kneller produced roughly 500 mezzotints, or about 300 copies of portrait paintings, while closely collaborating with John Smith, who is rumoured to have lived in his home for a while.

From approximately 1760 until the Great Crash of 1929, collecting British mezzotints was a huge fad that also expanded to America. During this time, British portraits were the most popular type of collecting; popular oil paintings from the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition were frequently and financially reproduced in mezzotint, while other mezzotinters copied earlier portraits of historical individuals or, if required, made their own. The golden period of the British portrait, roughly from 1750 to 1820, was the most popular time to collect. There were two main types of collection: those who focused on making a comprehensive collection of material within a specific range and those who sought perfection in condition and quality (which in mezzotints declines after a relatively small number of impressions are taken from a plate) as well as the many “proof states” that artists and printers had kindly provided for them since the beginning.

Ludwig von Siegen used this technique when creating his first mezzotints. Parts of the image that were to remain light in tone were kept smooth, and the metal plate was tooled to produce indentations. The print plate was added with areas of indentations for the areas of the print that were to seem darker in tone. This technique was known as the “Additive method.” Using this method, it was possible to immediately produce the picture by simply roughening a blank plate where the darker portions of the image should be. Mezzo-tinto, which is Italian for “half-tone” or “half-painted,” is a term used to describe mid-tones between black and white that can be produced by altering the degree of smoothness.

The most popular technique was going from dark to light. A metal plate, often made of copper, has its entire surface uniformly roughened either manually using a rocker or mechanically. The plate would seem completely black if it were printed at this point. The image is then produced by carefully smoothing specific regions of the metal plate’s surface with metal tools; the smoothed areas will print lighter than those that weren’t. Completely flattened portions won’t contain any ink at all; instead, they will print “white,” or the colour of the paper without ink. Working “dark to light” or “subtractive” approach is what is meant by this.

The finished plate is printed using either approach in the same way: the entire surface is inked, the ink is then removed from the surface, leaving ink only in the pits of the still-rough portions beneath the plate’s original surface. A sheet of paper is placed next to the plate in a high-pressure printing press, and the procedure is repeated.

Since the pits in the plate are not deep, only a few top-quality impressions (copies) can be produced before the tone quality starts to deteriorate as the press’s pressure smoothes them out. One or two hundred truly good impressions might be possible.

Mezzotint is renowned for the opulent quality of its tones for two reasons: first, a consistently finely roughened surface holds a lot of ink, allowing for the printing of deep solid colours; and second, the process of smoothing the plate with a burin, burnisher, and scraper enables the development of fine tonal gradations. The burnisher has a smooth round end similar to many spoon handles, but the scraper has a tool with triangular ends.

View mezzotint prints here.