“This is where as the blazing sun approaches, the fragrant wax that holds the feathers together becomes soft. She melts. Icarus can wave his bare arms in vain: deprived of wings, he can no longer sustain himself in the void. He calls his father, then disappears in the azure of the waves of this sea which has since been called the Icarian Sea.”

– Ovid, Metamorphoses

As the myth goes,* Icarus is the son of Daedalus, who built the Minotaur’s labyrinth in Crete for King Minos. When the king’s rival Theseus escapes from the labyrinth, Minos wrongly imprisons the craftsman, his assistant, and his son suspecting that they revealed the labyrinth’s secrets. Daedalus hatches a plan to flee by way of the sky, since Minos controlled both land and sea, creating wings from wax and feathers. He warns his son to avoid flying too low over the sea and getting the wings wet or too high and risking the wax melting under the sun’s heat. Unable to curb his hubris, Icarus flies higher and higher, ruining his wings and falling to his death. The fate of Icarus is a famed reference throughout the art world and where Picasso saw a pattern in the canon, he had to insert himself in the mix.

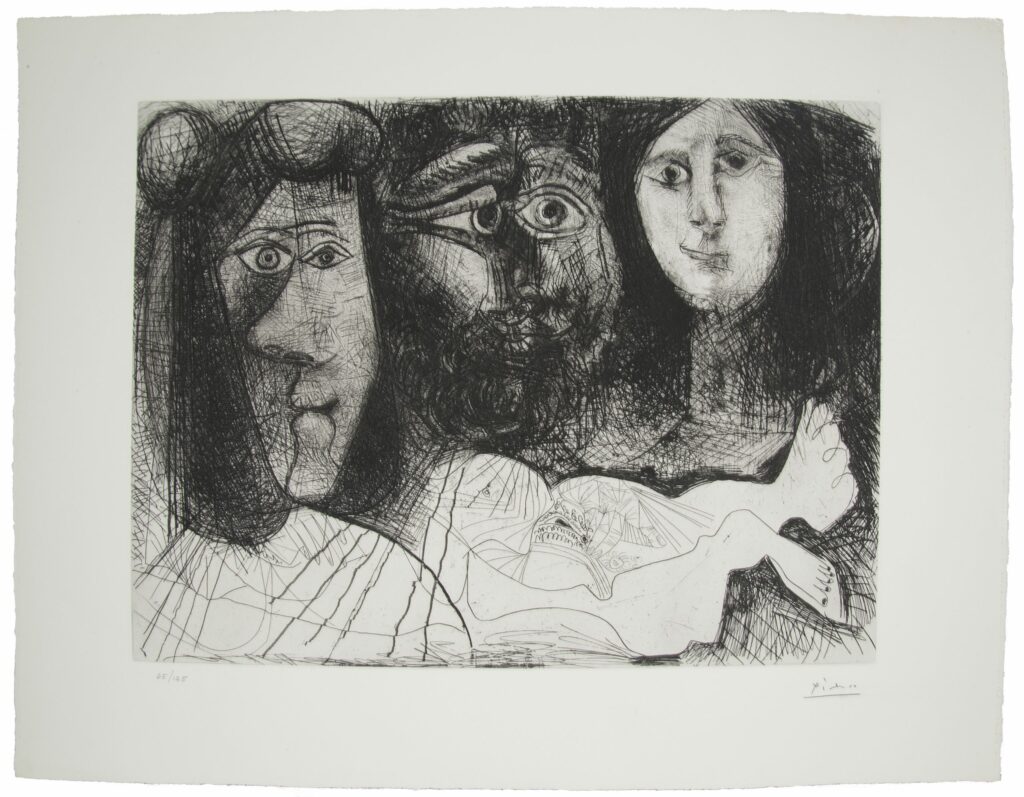

Picasso created multiple versions of The Fall of Icarus in various media. The first was produced in 1931 and came from a larger portfolio of etchings all depicting scenes from Metamorphoses. The second, a painting, was created as part of a larger series where he equated his contemporary world’s political struggles to the ancient world, another favorite theme in his oeuvre. He premiered this version at UNESCO’s Paris location, where its simplicity was not well received.** Perhaps this is why he revisited the same story 14 years later in today’s 1972 print.

Perhaps the most famous fall of Icarus painting is Pieter Brueghel the Elder’s version, titled Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (c. 1555). This scene places the Icarus myth in the background; at first glance, the unsuspecting viewer might not even recognize Icarus’ flailing legs in the water before observing the calm, pastoral scene before them. The indifference with which the surrounding landscape regards takes the mythic theme of hubris to new heights (pun intended). By placing the main character in a non-prominent role, Brueghel asks, what happens to greatness when it becomes lost in the crowd? Picasso’s Fall of Icarus print takes significant cues from Brueghel, placing Icarus amidst large, looming faces that emerge from the dark sky only to ignore the drowning boy with melted wigs below them.

Picasso was in his old age at the time of the print, begging the question: did he identify more with Icarus or Daedalus? It’s possible he saw himself as both, the master innovator and an older man who looks back at his overconfident, younger self with a greater sense of wisdom. Did he regret the moments when he (metaphorically, of course) drowned, or was he proud that he favored ambition (the sun) over complacency (the ocean)? Still, he situated Icarus as a small aspect of a larger, less exciting whole, perhaps alluding to the times he felt his most glorious work was overlooked in favor of the more palatable.

Courtesy of John Szoke Gallery, New York.