Details — Click to read

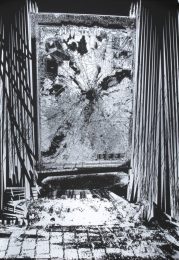

In 1976, a set of photographs from 1850 was discovered in a Harvard University storeroom. The daguerreotypes were commissioned by Harvard Professor Louis Agassiz, who was an adherent of “scientific racism”, to prove the inferiority of Black people. The photographs were taken by Joseph T. Zealy and are now known as the Zealy Daguerreotypes. The seven subjects of the photographs were enslaved Africans who lived in South Carolina, and were posed in both clothed and nude positions.

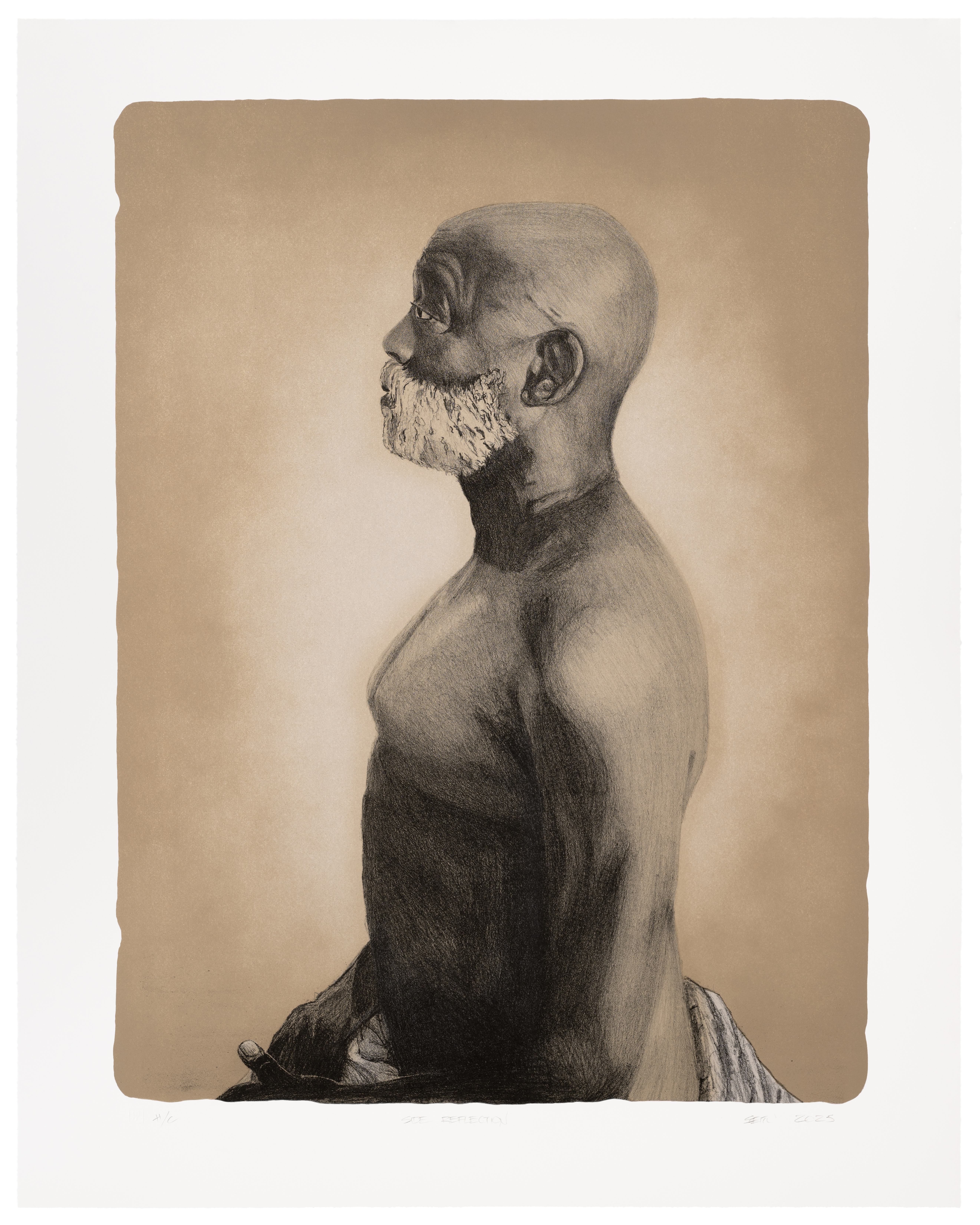

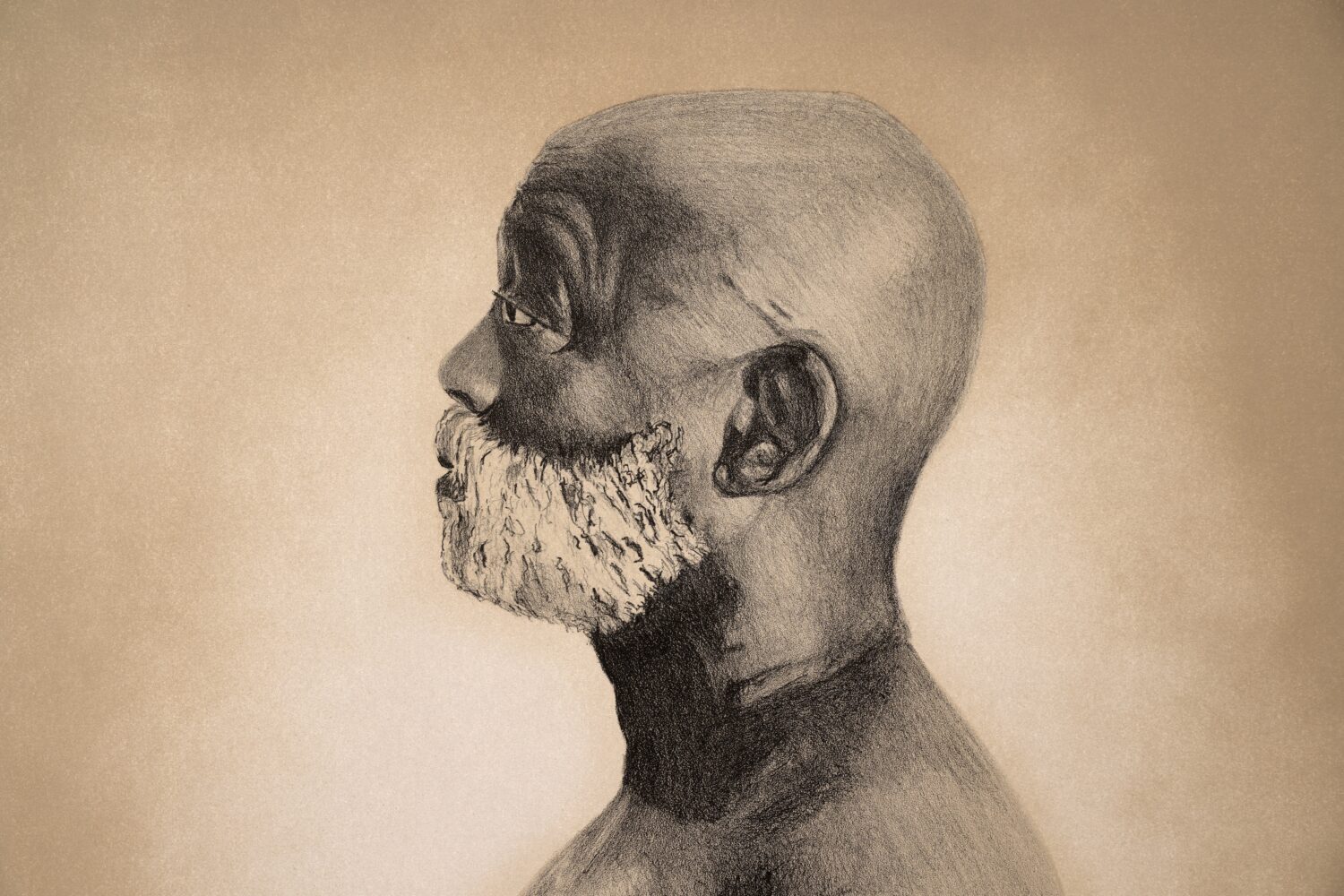

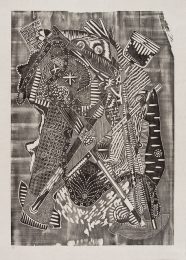

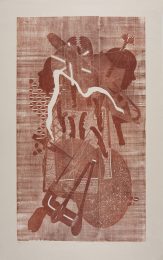

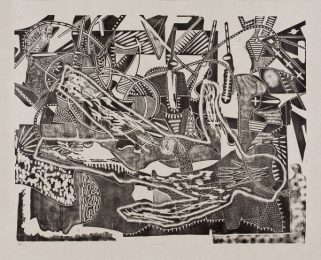

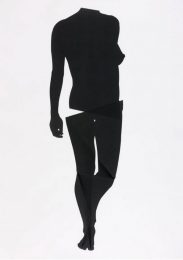

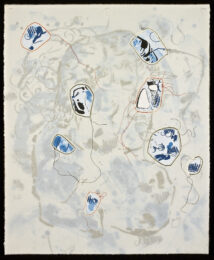

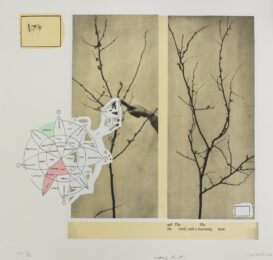

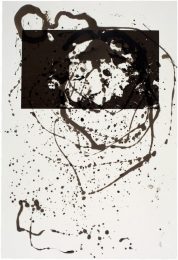

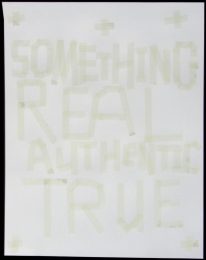

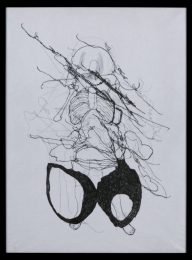

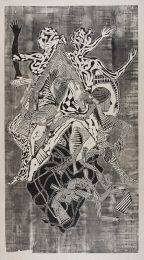

For the last 10 years, Seitu Ken Jones has painted and created a series of self-portraits that recall the experiences of African American men over the last 400 years. Inspired by the Zealy Daguerreotypes, Seitu’s prints mirror the degrading and disturbing images captured by the photographer. “Each daguerreotype reveals an individual, deeply dignified and expressive. Their hurt, contempt, fatigue, utter refusal are unequivocal,” says Parul Sehgal of the original images. In each of Seitu’s self-portraits, he reveals himself in the most dignified and resilient manner of those whom he honors. Jones places himself as the subject and the documentarian, recontextualizing the images as a symbol of humanity, history, and a continued fight for freedom and liberty.

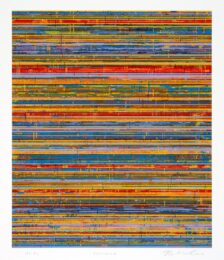

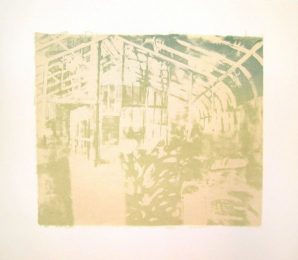

Each layer of the 7-run lithograph calls attention to the process. The outer borders mimic the irregular edges of the lithographic stones the artist drew on to create the portraits. While the coloring of the background can also be viewed as referencing the sepia tones of an aged daguerreotype, each layer is an homage to the materials used in processing lithographic stones. The layers of brown were matched to both the liquid asphaltum used before inking the stone, and the color of the stone after a thin layer of gum arabic has been buffed in to preserve the image. The transparent grey layer that makes up the background echoes the cool grey of the lithographic stone. The black of the lithographic crayon drawing is also iconic to the lithographic process and legacy; furthering these prints’ place as a contemporary reflection of historical statements and processes.