Colour Theory in Art: A Journey Through Chromatic Innovation

· blog

Colour theory stands as one of the most fundamental yet revolutionary concepts in the history of art, transforming not merely how artists approach their craft, but how viewers perceive and experience visual culture. From the earliest cave paintings to contemporary digital art, the understanding and manipulation of colour has evolved from intuitive application to sophisticated scientific principle, fundamentally altering the trajectory of artistic expression.

The Foundations of Colour Understanding

The systematic study of colour began to crystallise during the Renaissance, though artists had been intuitively exploring chromatic relationships for millennia. Sir Isaac Newton’s experiments with prisms in the 1660s provided the scientific foundation for understanding colour as light, establishing the visible spectrum and introducing the concept that white light contains all colours. This scientific breakthrough would later prove instrumental in how artists conceived of colour mixing and chromatic harmony.

The traditional colour wheel, based on the primary colours of red, yellow, and blue, emerged from centuries of practical experience among painters and craftsmen. However, it was the German poet and scientist Johann Wolfgang von Goethe who, in his 1810 work “Theory of Colours,” challenged Newton’s purely physical approach by introducing psychological and emotional dimensions to colour perception. Goethe’s insights into the subjective experience of colour would profoundly influence generations of artists seeking to harness colour’s emotive power.

Impressionism: The Liberation of Colour

The Impressionist movement of the late 19th century marked a watershed moment in the application of colour theory to fine art. Claude Monet, the movement’s principal architect, revolutionised landscape painting through his systematic exploration of light and atmospheric colour. His series paintings—including the Water Lilies, Rouen Cathedral, and Haystacks—demonstrate an almost scientific approach to documenting how colour transforms under varying conditions of light and weather.

Monet’s technique of applying pure colours directly to the canvas, allowing the viewer’s eye to optically mix them, was grounded in contemporary scientific understanding of colour perception. This approach, known as divisionism or pointillism when taken to its extreme, represented a radical departure from traditional academic practice of mixing colours on the palette before application.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir further developed these principles, though with a more intuitive approach that emphasised the warmth and sensuality of colour. His mastery lay in understanding how warm and cool colours could create depth and volume without relying on traditional chiaroscuro techniques. Renoir’s late works, particularly his bathers series, demonstrate an almost musical understanding of colour harmony, where hues seem to resonate and complement each other in sophisticated chromatic orchestrations.

Post-Impressionism: Colour as Emotion and Structure

The Post-Impressionist period witnessed colour theory’s evolution from purely observational tool to vehicle of emotional and structural expression. Paul Cézanne, often called the father of modern art, approached colour with architectural precision, using chromatic relationships to construct form and space. His revolutionary insight that colour could simultaneously describe light, form, and depth laid the groundwork for virtually all subsequent modern art movements.

Cézanne’s famous dictum to “modulate” rather than “model” reflected his understanding that colour temperature and intensity could create three-dimensional form more effectively than traditional light-and-shadow techniques. His still lifes and landscapes demonstrate how warm colours advance whilst cool colours recede, a principle that would become fundamental to modern colour theory.

Vincent van Gogh transformed colour into pure emotional expression, using chromatic intensity and contrast to convey psychological states. His understanding of complementary colours—those opposite each other on the colour wheel—enabled him to create vibrations and tensions that mirror his internal emotional landscape. Works such as “The Starry Night” and his Arles period paintings showcase how colour can transcend mere representation to become a language of feeling.

Paul Gauguin’s synthetic approach to colour, developed during his Pont-Aven and Tahitian periods, demonstrated how arbitrary colour choices could enhance rather than diminish artistic truth. His bold use of non-naturalistic colours influenced countless artists and established the principle that colour need not be descriptive to be meaningful.

Fauvism: Colour Unleashed

The Fauvist movement, led by Henri Matisse and André Derain, represented colour theory’s most radical early manifestation. These “wild beasts” of the art world liberated colour entirely from its descriptive function, using pure, unmixed pigments to create works of unprecedented chromatic intensity.

Matisse, arguably the greatest colourist of the 20th century, possessed an intuitive understanding of colour relationships that bordered on genius. His cut-out works from his later period demonstrate the ultimate synthesis of form and colour, where the two become indistinguishable. Matisse’s famous observation that he wanted to create art that would be “like a good armchair” for the tired businessman reveals his understanding of colour’s psychological impact.

The Fauvist exploration of simultaneous contrast—the phenomenon where colours appear different depending upon their neighbours—pushed colour theory into new territory. Their work demonstrated that colour could carry the entire expressive burden of a painting, making traditional concerns with perspective, modelling, and naturalistic representation secondary.

Abstract Expressionism and Colour Field Painting

The mid-20th century saw colour theory reach new levels of sophistication through the Abstract Expressionist movement. Mark Rothko’s colour field paintings represent perhaps the purest exploration of colour’s spiritual and emotional dimensions. His floating rectangles of colour, achieved through multiple transparent glazes, create meditative spaces where colour becomes the sole vehicle for transcendent experience.

Rothko’s meticulous attention to colour relationships, his understanding of how colours interact at their edges, and his sensitivity to scale and proportion demonstrate colour theory applied with almost mystical precision. His chapel paintings in Houston represent the culmination of a lifetime’s exploration into colour’s capacity to evoke the sublime.

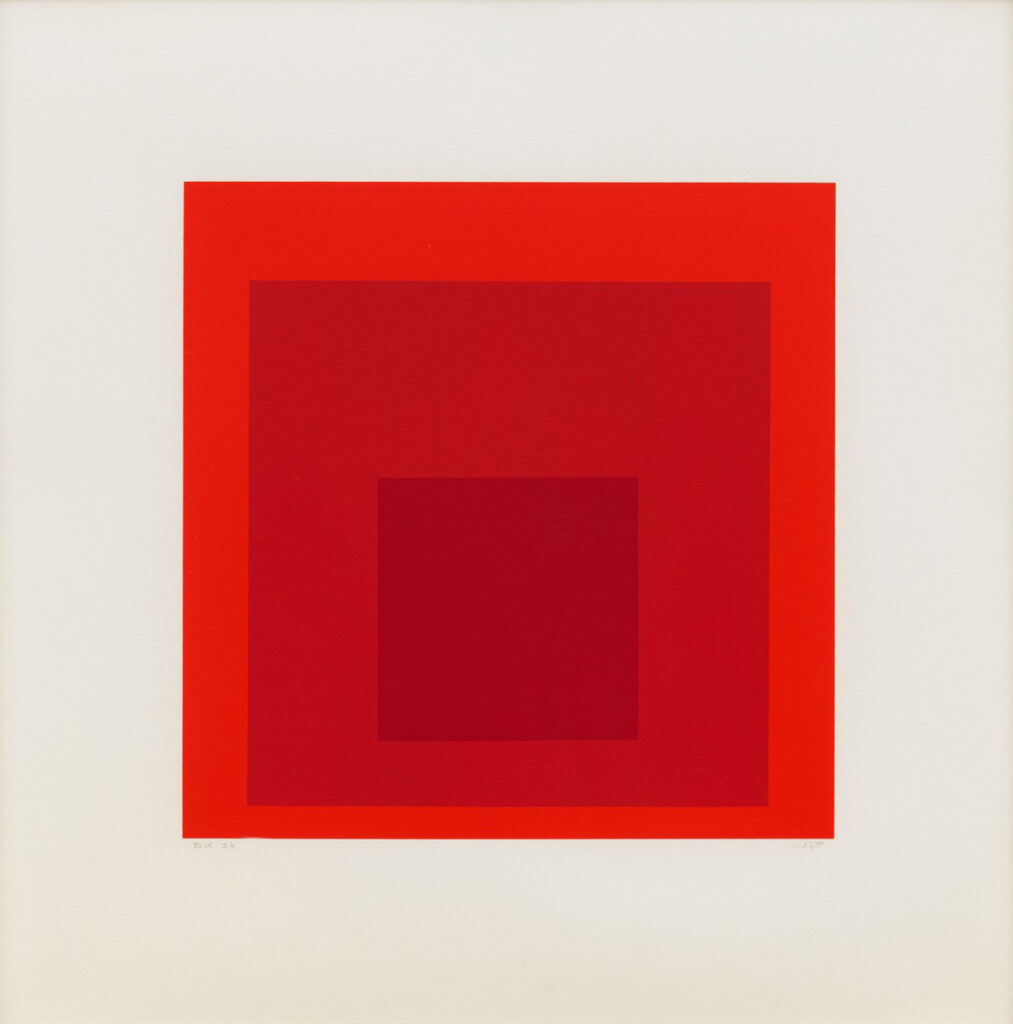

Josef Albers revolutionised colour theory through his “Homage to the Square” series and influential teaching at the Bauhaus and Yale. His systematic exploration of colour interaction demonstrated how identical colours appear different when surrounded by varying hues, establishing principles of simultaneous contrast that remain fundamental to contemporary colour education and practice.

Barnett Newman’s zip paintings explore similar territory through different means, using colour relationships and proportions to create what he termed “cathedrals out of ourselves.” His understanding of how a single vertical line could activate an entire colour field shows sophisticated appreciation for colour theory’s more subtle principles.

Helen Frankenthaler’s soak-stain technique, developed in the 1950s, allowed colours to interact in ways previously impossible, creating atmospheric effects that influenced a generation of colour field painters. Her innovations demonstrated how technique and colour theory could combine to create entirely new artistic possibilities.

Contemporary Developments and Digital Age Applications

Contemporary artists continue to push colour theory into new territories, aided by technological advances and cross-disciplinary research. Artists like David Hockney have embraced digital media to explore colour in ways impossible with traditional materials, whilst maintaining deep connections to art historical colour traditions.

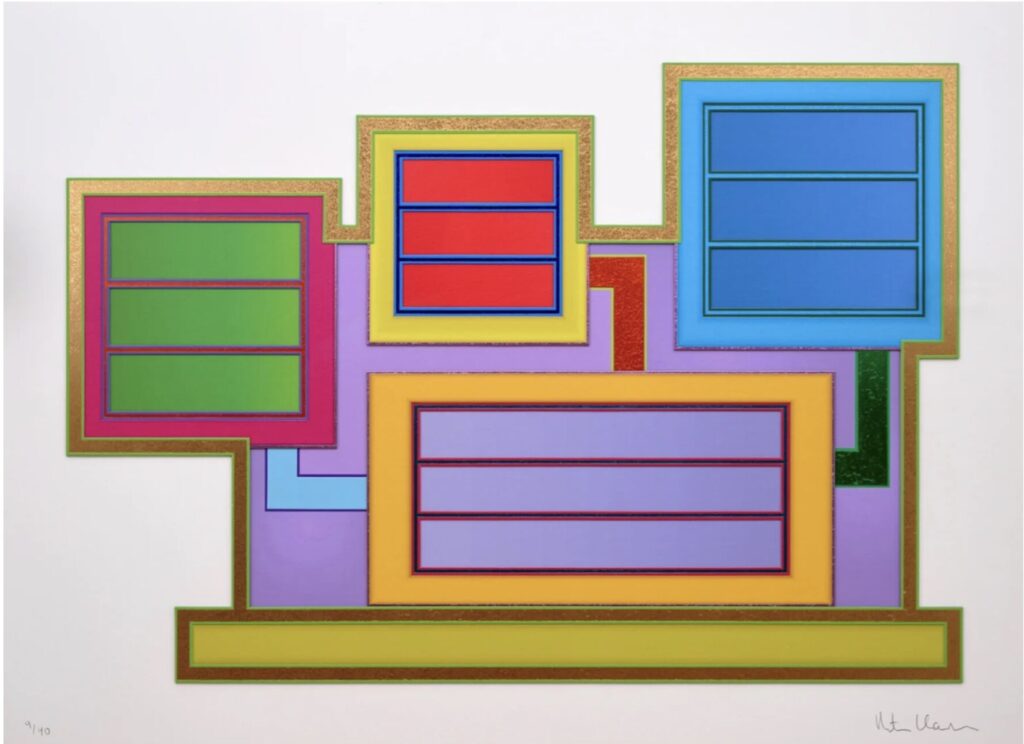

The work of contemporary painters such as Peter Halley demonstrates how colour theory continues to evolve, incorporating influences from popular culture, technology, and contemporary colour science. Halley’s day-glo and metallic paintings reference both minimalist colour field painting and contemporary urban visual culture.

Gerhard Richter’s squeegee paintings show how chance operations can be incorporated into sophisticated colour theory applications, whilst his colour chart works directly engage with commercial and scientific colour systems, questioning the boundaries between fine art and functional colour applications.

Scientific Advances and Artistic Innovation

Modern colour science has provided artists with unprecedented understanding of how colour perception actually works. Research into colour constancy, simultaneous contrast, and the neurological basis of colour perception has validated many intuitive discoveries made by artists whilst revealing new possibilities for chromatic manipulation.

The development of new pigments and digital colour technologies continues to expand artists’ palettes, whilst research into colour psychology provides new frameworks for understanding colour’s emotional and cultural impact. Contemporary artists increasingly draw upon this scientific knowledge whilst maintaining the essential artistic insight that colour’s ultimate meaning transcends purely technical considerations.

Conclusion: The Continuing Evolution of Colour

Colour theory in art represents one of humanity’s most sophisticated achievements in understanding the relationship between perception, emotion, and meaning. From Monet’s scientific observations of light to Rothko’s spiritual colour fields, from Matisse’s intuitive genius to contemporary digital innovations, artists have continuously pushed the boundaries of chromatic possibility.

The great colour theorists of art history—Monet, Cézanne, Matisse, Rothko, and countless others—have demonstrated that colour theory is not merely technical knowledge but a means of accessing fundamental aspects of human experience. Their investigations into colour relationships, emotional resonance, and perceptual phenomena have enriched not only art but our broader understanding of consciousness itself.

As we move forward into an increasingly digital age, colour theory continues to evolve, incorporating new technologies and scientific insights whilst maintaining its essential connection to the deepest aspects of human perception and emotion. The legacy of these pioneering artists ensures that colour will remain one of art’s most powerful and continuously evolving languages, capable of expressing the full range of human experience through the infinite possibilities of chromatic relationship and meaning.

The study of colour theory in art ultimately reveals that technical knowledge and artistic intuition are not opposing forces but complementary aspects of creative vision. The greatest colour theorists combined rigorous understanding of chromatic principles with profound sensitivity to colour’s emotional and spiritual dimensions, creating works that continue to inspire and influence artists and viewers alike. In this synthesis of science and art, technique and vision, colour theory represents one of the finest achievements of human creative endeavour.