From Light to Truth: The Transition from Impressionism to Naturalism in Printmaking

The emergence of Impressionism in the 1860s fundamentally transformed artistic expression, and printmaking became a crucial medium for exploring and disseminating these revolutionary ideas. Impressionist printmakers, led by figures such as Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt, and Camille Pissarro, embraced the medium’s inherent qualities to capture fleeting moments and atmospheric effects. Unlike traditional printmaking, which emphasised precision and classical subject matter, Impressionist prints sought to convey the immediacy of visual experience through innovative techniques and unconventional compositions.

The Impressionists’ approach to printmaking was characterised by their experimental use of traditional techniques such as etching, aquatint, and lithography. They exploited the medium’s capacity for subtle tonal variations and textural effects, using them to render the play of light and shadow that was central to their aesthetic philosophy. Degas, in particular, revolutionised printmaking through his innovative use of monotype, a technique that allowed for unique, painterly effects that perfectly complemented the Impressionist desire to capture transient moments. His ballet dancers and café scenes demonstrated how printmaking could achieve the spontaneity and luminosity typically associated with painting.

Technical Innovation and Artistic Expression

The technical innovations introduced by Impressionist printmakers laid crucial groundwork for the subsequent development of more naturalistic approaches. Their willingness to experiment with non-traditional methods, such as combining different printmaking techniques within a single work or manipulating plates in unconventional ways, expanded the expressive possibilities of the medium. Pissarro’s collaboration with his son Lucien in developing colour etching techniques exemplified this experimental spirit, creating prints that could rival paintings in their chromatic sophistication.

These technical advances were not merely formal exercises but served deeper artistic purposes. The Impressionists’ emphasis on capturing the effects of natural light through printmaking required them to develop new approaches to tone, texture, and composition. Their innovations in areas such as à la poupée wiping (selective inking) and creative use of paper tone became foundational techniques that later naturalist printmakers would adapt and refine for their own expressive needs.

The Emergence of Naturalist Sensibilities

As the 19th century progressed, a growing dissatisfaction with Impressionism’s perceived subjectivity and emphasis on visual sensation gave rise to naturalist tendencies in printmaking. This transition was not abrupt but rather represented a gradual shift towards greater emphasis on social realism, documentary accuracy, and the depiction of contemporary life in its unvarnished reality. Naturalist printmakers, whilst retaining many of the technical innovations pioneered by the Impressionists, redirected these tools towards more socially conscious and objectively observational ends.

The naturalist movement in printmaking found its most compelling expression in the work of artists who sought to document the realities of modern urban and industrial life. Unlike their Impressionist predecessors, who often focused on leisure activities and bourgeois pleasures, naturalist printmakers turned their attention to working-class subjects, industrial landscapes, and social conditions. This shift represented not merely a change in subject matter but a fundamental reorientation of artistic purpose, from the celebration of sensory experience to the critical examination of social reality.

Bridging Movements: Shared Techniques, Divergent Purposes

The transition from Impressionism to Naturalism in printmaking was facilitated by the fact that both movements shared certain technical preferences and innovations, even as they diverged in artistic philosophy. Both movements valued the directness and immediacy that printmaking could offer, particularly in techniques such as drypoint and lithography, which allowed for spontaneous, sketch-like effects. However, whilst Impressionists used these qualities to capture fleeting atmospheric conditions, naturalists employed them to create a sense of documentary authenticity and social immediacy.

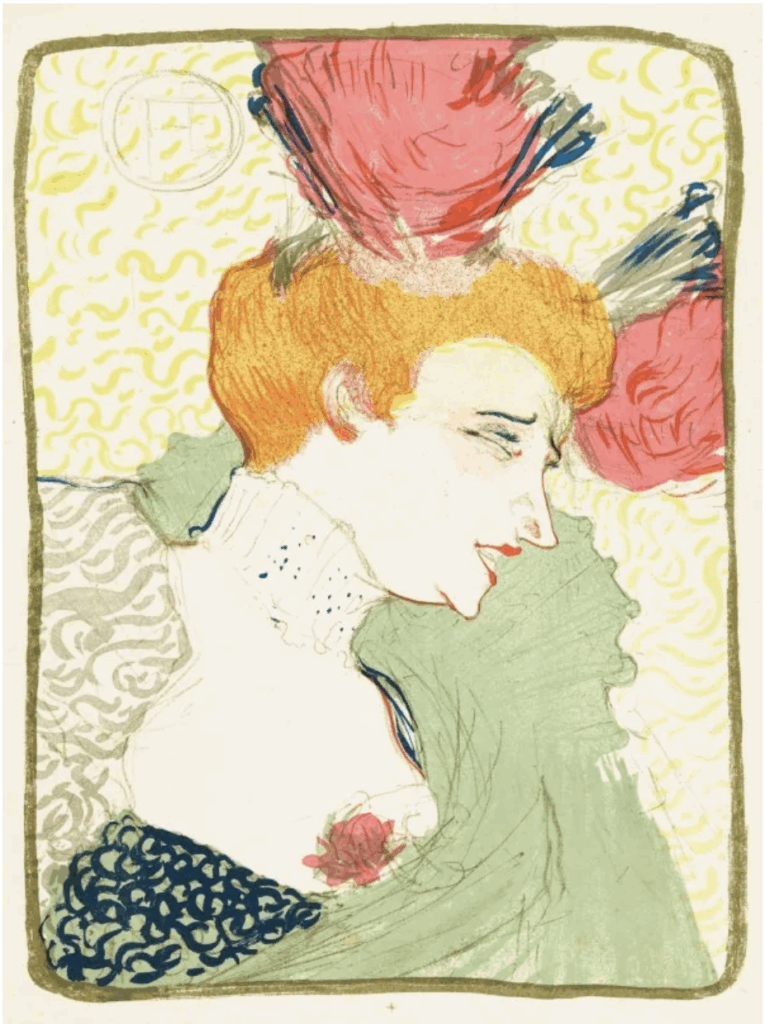

The lithographic medium proved particularly conducive to this transition, as its capacity for both subtle tonal gradations and bold, graphic effects could serve either Impressionist or naturalist purposes. Artists such as Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec demonstrated how lithography could be adapted from the Impressionist tradition of capturing light effects to the naturalist goal of social commentary. Steinlen’s prints of Montmartre life retained the technical sophistication developed during the Impressionist period whilst redirecting that expertise towards more pointed social observation, particularly in his depictions of working-class cabarets and street scenes. Similarly, Toulouse-Lautrec’s lithographic posters, whilst maintaining the Impressionist fascination with urban entertainment, increasingly revealed the darker undercurrents of Parisian nightlife. Meanwhile, Honoré Daumier, though predating both movements, served as a crucial bridge figure whose satirical lithographs influenced naturalist printmakers’ approach to social critique through graphic art.

The Role of Urban Subject Matter

One of the most significant aspects of this transition was the evolving treatment of urban subject matter. Impressionist printmakers had certainly depicted city life, but their focus typically remained on its more pleasant or visually striking aspects—the grand boulevards, fashionable cafés, and theatrical entertainments that characterised modern Paris. Naturalist printmakers, by contrast, sought to reveal the full spectrum of urban experience, including its poverty, labour, and social tensions.

This shift in focus required new approaches to composition and technique. Naturalist printmakers developed strategies for depicting crowded, complex urban environments with greater detail and social specificity than their Impressionist predecessors had attempted. They employed the technical vocabulary established during the Impressionist period but adapted it to serve documentary rather than purely aesthetic purposes, creating prints that functioned as both artistic statements and social documents.

Legacy and Lasting Influence

The transition from Impressionism to Naturalism in printmaking established patterns of technical innovation and thematic development that would influence subsequent generations of printmakers. The experimental spirit fostered during the Impressionist period created a foundation of technical possibility that naturalist artists could build upon, whilst the naturalists’ commitment to social engagement expanded the conceptual framework within which printmaking could operate.

This evolution also demonstrated printmaking’s unique capacity to serve multiple artistic and social functions simultaneously. The medium’s reproducibility made it particularly well-suited to the naturalists’ democratic ideals and desire to reach broader audiences, whilst the technical sophistication developed during the Impressionist period ensured that these socially engaged works maintained the highest artistic standards. The synthesis of technical innovation with social consciousness that characterised this transition continues to influence contemporary printmaking, establishing printmaking as a medium capable of both aesthetic sophistication and social relevance.