The Woodcuts of Wassily Kandinsky

Forging the Path to Abstraction

Wassily Kandinsky’s woodcuts represent far more than a subsidiary aspect of his artistic production. These remarkable works served as an experimental laboratory where the Russian-born artist worked through fundamental questions about form, space, and perception that would ultimately revolutionise modern art. Whilst Kandinsky is justly celebrated for his groundbreaking abstract paintings, his engagement with woodcut printmaking reveals a crucial dimension of his artistic development, demonstrating how traditional techniques could be transformed to serve radical new purposes in the early twentieth century.

Early Experiments in Reduction and Simplification

Kandinsky’s initial woodcuts, created during the first decade of the twentieth century, already reveal his fascination with simplified, expressive forms. From the beginning of his artistic career, Kandinsky experimented with different media and techniques, with his studies at the Ažbe-Schule and at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich exposing him to a variety of Jugendstil practices and theories on form, colour, and figural types. The woodcut medium proved particularly suited to his developing interests, as the very process of carving wood demanded a reduction of visual complexity.

One of his notable early works, “Ewigkeit” (Eternity) from 1903, exemplifies this experimental approach. Consisting of a path winding from the lower left-hand corner to the door of a building at centre and trees silhouetted against a large sun emitting broad rays, the work is dominated by sharp contrasts between positive and negative spaces. What makes this piece particularly significant is how it functions on multiple levels – as both a recognisable landscape and as a composition of flat patterns and geometric shapes. The simplified lines indicating windows and doors create optical effects that would become increasingly important in Kandinsky’s work.

The Psychology of Visual Perception

A crucial aspect of Kandinsky’s woodcut practice was his engagement with contemporary psychological theories about vision and perception. His use of practices in his art is consonant with psychological studies in visual perception that were developing concurrently, in which psychologists theorised about how the eye and mind interpret a complete visual field, with leaders in this new discipline including Wilhelm Wundt, Christian von Ehrenfels, and Theodor Lipps. These scientific investigations into how humans process visual information profoundly influenced Kandinsky’s artistic direction.

By 1907, works such as “Hügel, Baum, Wolken und Figur” (Hill, Trees, Clouds, and Figure) demonstrated increasingly sophisticated manipulation of spatial relationships. Kandinsky carved away more of the woodblock, reversing the proportion of positive to negative space and printing lines and contours in black, with the main focus being the visual interplay of repeated forms. The artist deliberately flattened the pictorial space and created patterns that make foreground and background nearly interchangeable. This technique anticipates principles that would later be formalised by psychologist Edgar Rubin in his famous figure-ground studies, suggesting that Kandinsky possessed an intuitive understanding of visual perception’s complexities.

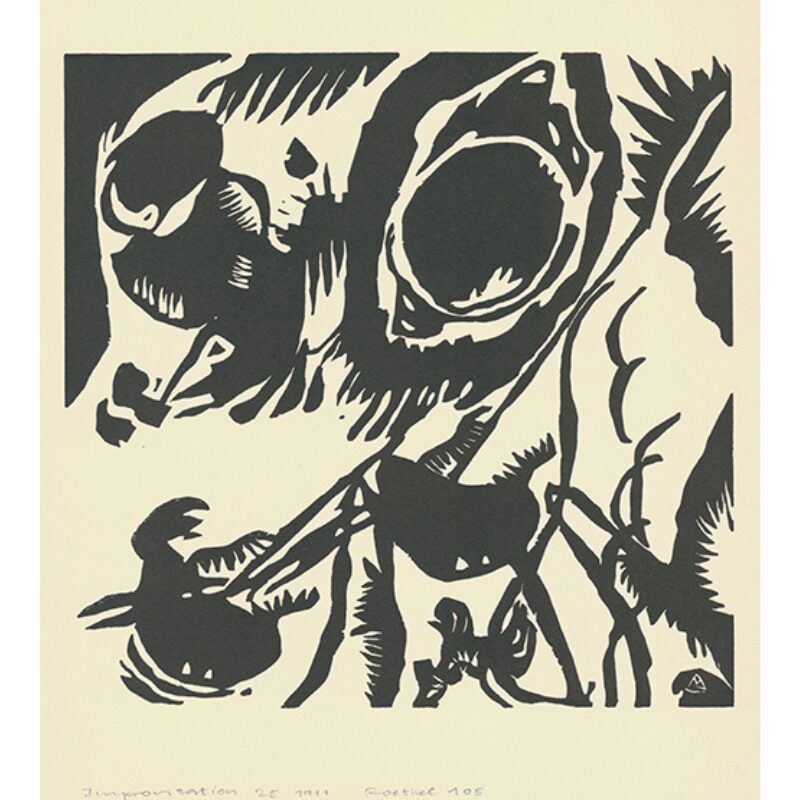

The Journey Towards Pure Abstraction

By 1912, Kandinsky’s woodcuts had evolved significantly towards complete non-objective imagery. His print “Offen” (Open) from that year represents a watershed moment. Without a discernible subject, Kandinsky’s work is dynamic in its arrangement, challenging the eye to perceive the image in its entirety at a single glance whilst simultaneously processing the details and disparate lines, making ordered sense of what might otherwise be seen as a fragmented cluster of shapes. This composition demonstrates his full embrace of abstraction, presenting a visual field composed entirely of lines, shapes, and patterns without reference to the external world.

The evolution visible across these three woodcuts – from the still-recognisable landscape of “Ewigkeit” through the ambiguous spaces of “Hügel, Baum, Wolken und Figur” to the complete abstraction of “Offen” – charts Kandinsky’s methodical progression towards his revolutionary artistic language. These three prints reveal Kandinsky’s early experiments in distilling, simplifying, and reconfiguring forms and in delineating and distorting space in a modern and distinctly unnatural way.

Klänge: A Gesamtkunstwerk

The culmination of Kandinsky’s early woodcut experiments arrived with the 1913 publication of “Klänge” (Sounds), one of the most significant artist’s books of the twentieth century. This portfolio combined fifty-six woodcuts – forty-four in black and white and twelve in colour – with Kandinsky’s own prose-poems. Theorist and painter in equal parts, Kandinsky’s experiments with abstract art were the result of years of self-analysis, technical development, and close observation of the effects colours and forms produced.

“Klänge” represented Kandinsky’s vision of a total work of art, or Gesamtkunstwerk, where visual and literary elements would combine to create a synesthetic experience. Each woodcut was conceived not merely as an illustration but as a visual equivalent to the accompanying text, creating resonances between word and image that would engage multiple senses simultaneously. The colour woodcuts in this series demonstrate remarkable technical sophistication, with each colour requiring a separate carved block, yet achieving complex chromatic interactions that prefigure his later painted compositions.

Technical Characteristics and Innovations

Kandinsky’s approach to woodcut technique exploited the medium’s inherent qualities whilst pushing its boundaries. The process of woodcut naturally encourages bold simplification and strong contrasts, characteristics that aligned perfectly with his developing abstract vocabulary. He understood how to manipulate the balance between carved and uncarved areas to create dynamic tensions, and his colour woodcuts reveal a sophisticated grasp of how different hues interact when printed in layers.

In his woodcuts Kandinsky could challenge and play with scale and proportion, relative sizes and shapes of objects, and depth perception, tactics he would continue to experiment with throughout his career. The woodcut’s tendency to flatten space and reduce forms to their essential shapes became tools for Kandinsky rather than limitations, enabling him to investigate the fundamental components of visual language.

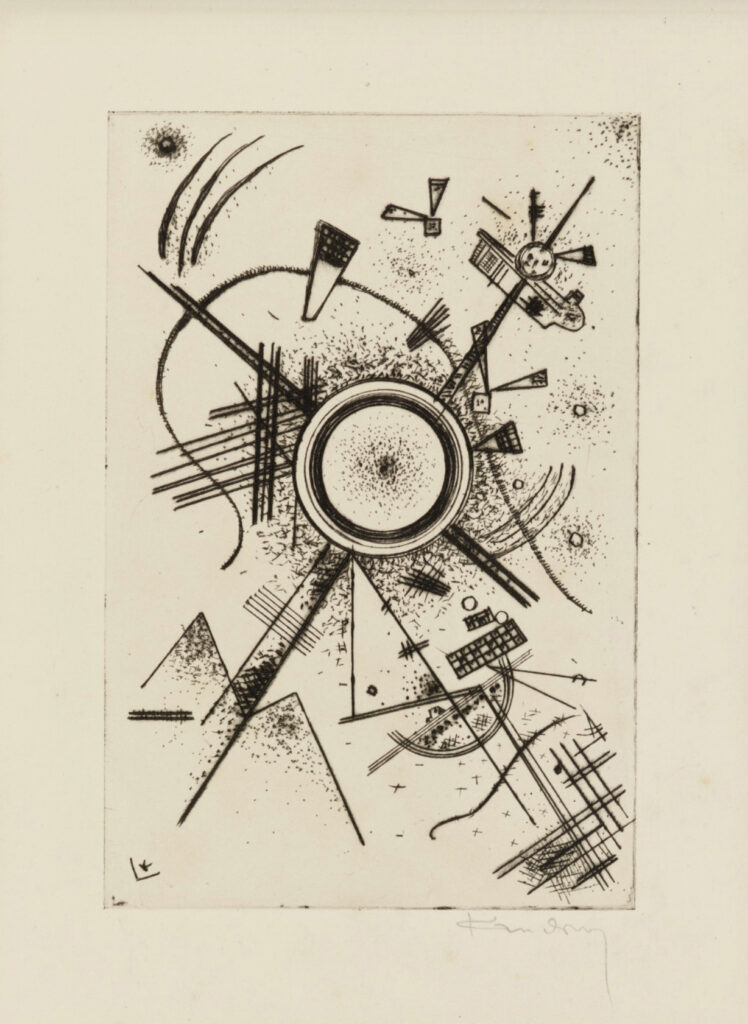

Kleine Welten and Comparative Techniques

Following “Klänge”, Kandinsky created the “Kleine Welten” (Small Worlds) portfolio in 1922, which offers unique insights into his printmaking philosophy. This series comprises twelve prints divided equally between three techniques: drypoint, lithography, and woodcut. The woodcuts within this portfolio demonstrate how the medium’s particular qualities – its textural richness, its bold contrasts, and its capacity for creating depth through layering – produced effects distinct from the other processes.

Each technique in “Kleine Welten” was selected specifically for its expressive potential, and the woodcuts show Kandinsky’s continued exploration of how the physical act of carving into wood could generate particular visual effects. The portfolio’s title suggests that each print constitutes a complete world unto itself, with meaning generated exclusively through formal elements rather than representation.

Theoretical Foundations

Kandinsky’s woodcuts cannot be separated from his theoretical writings, particularly his seminal text “Über das Geistige in der Kunst” (Concerning the Spiritual in Art), first published in 1911. In this treatise, he articulated his belief that art should communicate spiritual truths through pure formal means rather than through representation of the material world. The woodcut medium, with its inherent tendency towards simplification and abstraction, provided an ideal vehicle for realising these theories.

Kandinsky formulated similar principles about perception and aesthetics in his own treatise on art, relating to psychological studies that explored how the mind seeks to counter-balance visual chaos by means of distilling pictorial fields into rudimentary forms. His woodcuts thus served as practical demonstrations of his theoretical positions, showing how abstract compositions could create meaningful aesthetic experiences without recourse to recognisable imagery.

Historical Significance and Legacy

Kandinsky’s woodcuts occupy a crucial position in the history of both printmaking and abstract art. They demonstrate how a traditional medium associated with folk art and illustration could be transformed into a vehicle for avant-garde experimentation. Compositions that predate his fully abstract works already show his preoccupation with unmodulated forms, reductive geometry, and recurring patterns as he created a new visual syntax that would serve as the basis of uniquely innovative, geometric-optical structures defining Kandinsky’s contribution to abstract art in the first decades of the twentieth century.

The influence of these works extends beyond Kandinsky’s immediate circle to affect the entire trajectory of twentieth-century printmaking. By demonstrating that woodcuts could serve as primary artistic statements rather than merely reproductive tools, Kandinsky established printmaking as a legitimate medium for serious artistic investigation. His integration of text and image in “Klänge” anticipated later developments in conceptual art and artist’s books, whilst his technical innovations showed how traditional processes could be adapted to contemporary artistic purposes.