Guide For Print Collectors: What Is a Print?

What is a Print?

The term “print” is sometimes used to describe just about any picture that is not an original painting or drawing. Photographs, cheap posters, reproductions in art books…. Some people refer to all of these as “prints”.

In the art world, the word “print” has a far more specific meaning, and anyone buying prints must understand that meaning.

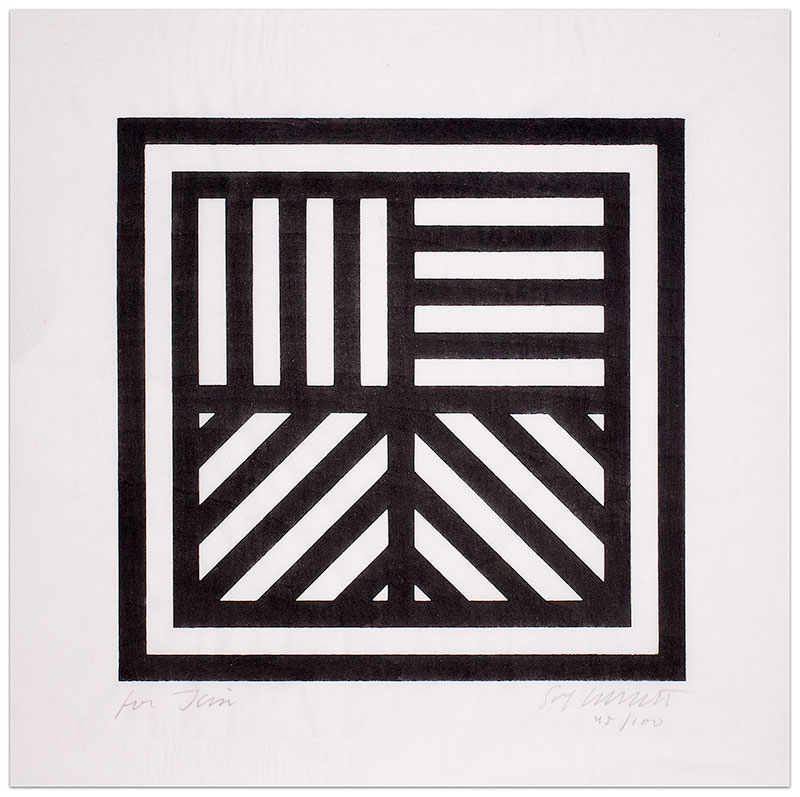

When an artist wants to make a print, he must start by creating an image on a matrix. There are three kinds of prints:

Relief prints

The matrix is usually a block of wood (in which case the prints are called “woodcuts” or “wood engravings”) or a sheet of linoleum (in which case the prints are called “linoleum cuts” or “linocuts”). Many of us made “potato prints” when we were schoolchildren: we cut a potato in half, engraved a design onto the flat surface, inked it, and printed it on paper. This is a kind of relief print.

Intaglio prints

The matrix is a sheet of metal, usually copper or zinc. Depending on the method of engraving, the prints are called “burin engravings”, “etchings”, drypoints”, “aquatints”, or “mezzotints”.

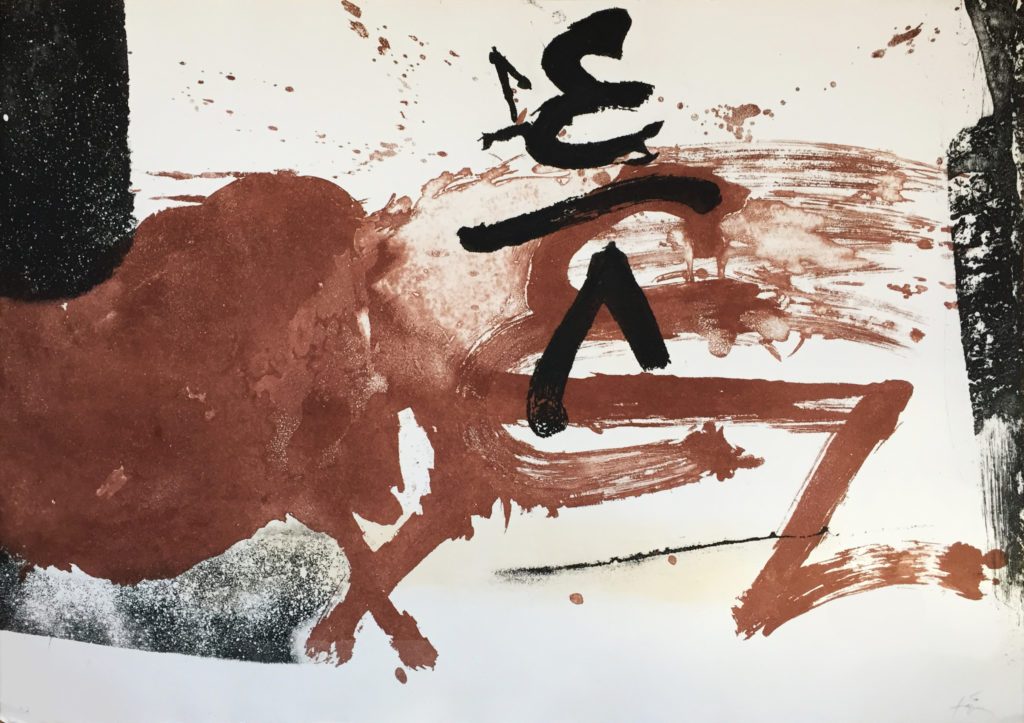

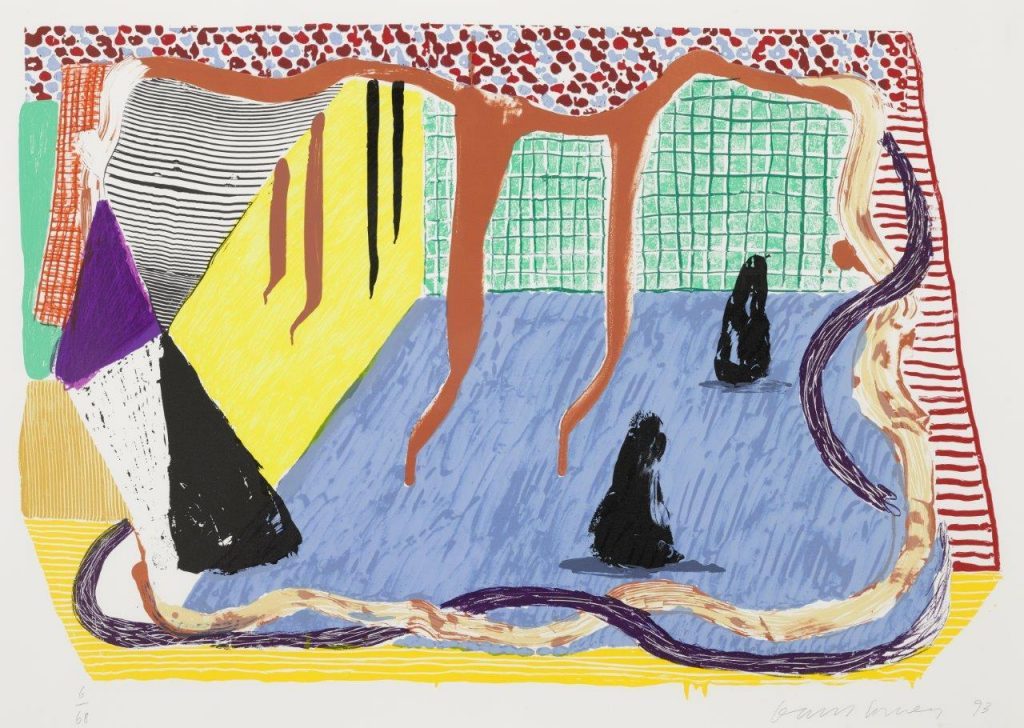

Planographic prints

The matrix is either a flat, porous stone (like limestone) or a sheet of treated metal, usually zinc. The prints are called “lithographs” (although some people use the term “zincographs” if the matrix is zinc). Silkscreen prints (also called “serigraphs” or “seriagraphs”) are also planographic, but experts debate whether silkscreen prints are true prints or mere reproductions.

Once the artist has prepared the matrix, the printer inks the matrix and prints it on paper. The sheet of paper becomes a PRINT. It bears the image on the matrix, although the image is laterally inverted (i.e., “mirror-style”), just like a rubber stamp. The matrix can then be inked and printed again, on another sheet of paper, and each print from this matrix will be substantially identical.

Perhaps the printer will print ten prints from the matrix; that would be a small edition. Perhaps he will print 300; that would be a large edition. Perhaps he will print 10,000.

Note that each print is printed directly from the matrix prepared by the artist.

Some artists create original prints (rather than simply painting and sculpting) because they enjoy exploring the unique artistic possibilities afforded by printmaking. Other artists simply use printmaking to create artworks that are far less expensive than paintings and sculptures, and thus can reach a different market. Personally, I seek out works by artists—of all periods—in the former category: those who have explored (and sometimes revolutionized) the printmaking techniques and processes.

Another technique for creating multiple images of an artist’s work is photomechanical reproduction. What this means is that someone simply reproduces the work of an artist by photographic means. There is no need for the artist to be involved in this process: he might even be dead. The reproductions are not “originals” in any sense of the word, even if they are signed. While sometimes these reproductions have sophisticated-sounding names (“giclées”, “offset lithographs”, “photolithos”, “heliogravures”, “collotypes”, “photogravures”, “heliotypes”, etc.), they are just glorified photocopies, and have the same artistic significance: none.

Serious collectors have absolutely no interest in photomechanical reproductions.

Example: the “Vollard Suite” is a set of 100 intaglio prints created by Picasso from 1930 to 1937. Since the 1950s, various publishers have issued heliogravure facsimiles of this set. The original prints are valuable; the heliogravure facsimiles are worthless junk.

Another example: some very fine reproductions of Picasso linocuts have been published, especially by the Galerie Louise Leiris in Paris. They are very attractive, but they are simply reproductions. Some crooks tear these out of books and forge Picasso’s signature on them (and sometimes they forge the numbering as well). But if you check the catalogue raisonné (by Brigitte Baer, in this case), you will see that these reproductions are not the same size as the originals, nor are they printed on the same type of paper. They are worthless. The authentic linocuts, I might mention, can sometimes be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

About the author

Dr William Cole, a recognised expert in art connoisseurship, is director of the Sylvan Cole Gallery. His articles have appeared in Print Quarterly, Art in Print, Word & Image, and other leading journals. His most recent book is a catalogue raisonné of the illustrated books and print portfolios of Masafumi Yamamoto.