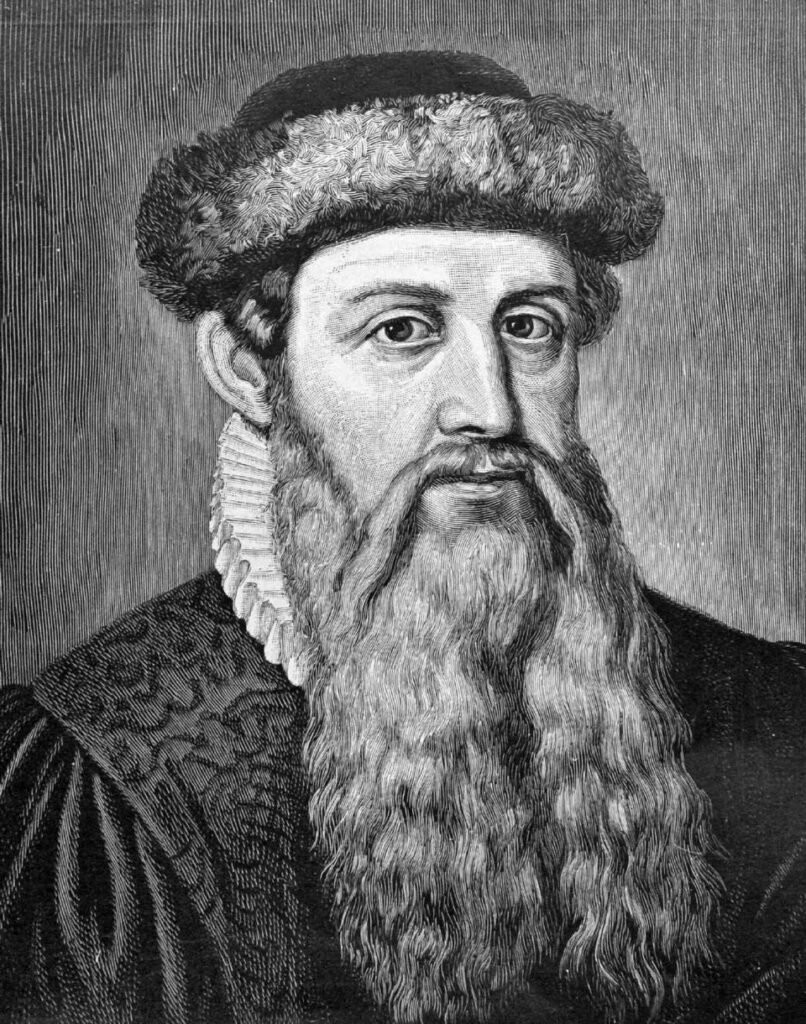

Johannes Gutenberg & The Printing Press

Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press emerged from a unique convergence of his background, professional expertise, and the social circumstances of 15th-century Mainz. Born around 1400 into a patrician family involved in the cloth trade and ecclesiastical mint, Gutenberg possessed both the social connections and financial resources necessary for such an ambitious undertaking. His father, Friele Gensfleisch, worked with the archbishop’s mint, exposing young Johannes to metalworking techniques that would prove crucial to his later innovations. The family’s relative prosperity meant Gutenberg received a solid education, likely at the University of Erfurt, where he would have encountered the scholarly demand for books that his invention would eventually satisfy.

Gutenberg’s professional life as a goldsmith and metalworker provided him with the technical foundation essential for creating movable type. His expertise in working with precious metals, understanding alloy compositions, and crafting precise small objects directly translated to the challenges of creating durable, uniform letter forms. During his time in Strasbourg in the 1430s and 1440s, he experimented with various printing techniques and formed partnerships with local investors who recognised the commercial potential of his ideas. These business relationships, though sometimes fraught with legal disputes, provided the capital necessary for his extensive research and development work.

The social and intellectual circles of Mainz in the mid-15th century created an ideal environment for Gutenberg’s innovation. The city was a significant ecclesiastical centre with a thriving community of scribes, scholars, and clergy who understood the immense value of books and the limitations of hand-copying manuscripts. Gutenberg moved within networks of learned churchmen, wealthy merchants, and skilled craftsmen who could both appreciate his vision and provide practical support. His partnership with Johann Fust, a wealthy merchant and moneylender, proved particularly crucial, as Fust’s financial backing enabled Gutenberg to pursue his work on a scale impossible for an individual craftsman.

The physical creation of the printing press represented a masterful synthesis of existing technologies adapted for a revolutionary new purpose. Johannes Gutenberg modified the design of wine and cheese presses, familiar throughout the Rhine valley, to create a mechanism capable of applying even pressure across a sheet of paper. His most significant innovation lay in developing a reliable system for movable type, which required solving numerous metallurgical challenges. He created a special alloy of lead, tin, and antimony that would cast sharp, durable letters whilst remaining malleable enough for repeated use. Each piece of type had to be precisely the same height to ensure even printing, requiring extraordinary precision in the casting process.

The technical innovations extended to every aspect of the printing process. Gutenberg developed oil-based inks that would adhere properly to metal type and transfer cleanly to paper, departing from the water-based inks used by scribes. He experimented with different papers and printing techniques to achieve the clarity and consistency that would make printed books competitive with the finest manuscripts. The famous 42-line Bible, completed around 1455, demonstrated the full realisation of his vision, combining technical excellence with aesthetic beauty that rivalled the work of the most skilled manuscript illuminators. This achievement represented not merely a mechanical innovation, but a complete reimagining of how knowledge could be preserved, reproduced, and disseminated throughout European society.